Treatment of Constipation (bian bi 便秘) with Chinese Medicine

This article is an excerpt from the Clinical Handbook of Internal Medicine: The Treatment of Disease with Traditional Chinese Medicine, Volume 2 by Will Maclean and Jane Lyttleton. While the book contains sections that discuss herb and formula recommendations, for compliance reasons those sections cannot be presented by Mayway. Please see the book for this information.

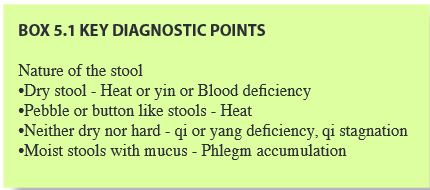

Constipation (bian bi 便秘) is difficulty in passing stools, prolonged intervals between stools, or a desire to defecate without the ability to do so partially or completely. The stools may be hard, dry and pebble like, or essentially normal (that is, moist and well formed).

People have widely varying ideas as to what constitutes a normal bowel pattern, and it must be established what the patient means when describing bowel movements. To some individuals, one motion per week is normal, while others consider themselves constipated if they defecate only once daily. In TCM the baseline for ‘normal’ is at least one unforced stool every day or second day. Establishing precisely what a patient means by constipation, in terms of frequency, sensation and the nature of the stools is essential.

Constipation is a common problem, and in the Western world appears to be largely related to diet and sedentary habits. Constipation can also be an acute event associated with other primary illnesses, typically those characterised by fever or dehydration. In these situations however, the constipation itself is unlikely to be the presenting problem, although it will certainly be considered in the treatment strategy. More commonly in the Western clinic, constipation is a chronic problem, often of many years duration.

Constipation can be broadly divided into two types, excess and deficient. The excess patterns are characterized by the presence of a pathogen (typically Heat or Phlegm) or by pathological accumulation of qi that blocks the qi mechanism and the descent of Large Intestine qi.

The deficient patterns are characterized by dryness from insufficient fluid lubrication in the form of body fluids, Blood or yin, or lack of propulsion through the digestive tract from deficiency of qi or yang.

ETIOLOGY

Heat

Heat causing constipation can be of external or internal origin. When external Heat causes constipation, it may be systemic Heat (as in Heat in the Blood), or more commonly, Heat in the qi level, that is, Heat invasion of the Lungs and/or Stomach and Intestines.

External Heat

Heat in the Lungs

Invasion of an external Heat pathogen, or other pathogen which transforms into heat once in the body, will dry body fluids and parch those parts of the body most sensitive to dryness, the Lungs and Intestines. A Heat pathogen in the Lungs, for example Phlegm Heat or Lung Fire, will dry both the Lungs and Intestines (through their yin yang relationship) and obstruct the descent of Lung qi. Indeed, other pathogens may also contribute to constipation by obstructing the descent of Lung qi, thus impeding Large Intestine qi movement. The drying power of Heat makes it by far the most common external pathogen to cause constipation. This is the type of constipation that frequently accompanies upper respiratory tract infections such as bronchitis and pneumonia. In these cases however, the constipation is unlikely to be the presenting disease symptom; much more likely the presenting disease will be cough, fever or wheezing.

Heat in the Stomach and Intestines (yang ming fu syndrome, and variations)

Heat invasion of the Stomach and Large Intestine is described as yang ming syndrome. The earliest description, by Zhang Zhong-Jing, circa 200 AD, relates to an invasion of Cold through the most exterior of the six levels (liu jing 六經) into either the yang ming channels or organs. The Cold transforms into Heat once through the surface and then lodges in the interior. These yang ming patterns are acute disorders that usually follow an unresolved or powerful Wind Cold or Wind Heat surface invasion, and are characterized by the ‘four bigs’-big fever, thirst, sweat and pulse. When the yang ming organs are affected, constipation is the main additional feature, and it is the purging of the constipation that is the key to eliminating the Heat (through the ‘big exit’). Pathogens may overlap two or more levels, for example the shao yang and yang ming levels, or all three yang levels. Specific formulae have been developed to treat these variations.

Internal Heat

The most common cause of internal Heat type constipation is diet (see below). Internal Heat can also be generated by prolonged frustration, resentment, or other emotional turmoil that impedes the movement of Liver qi. The transformation of stagnant qi into Heat is aided by consumption of heating foods and beverages, especially alcohol, rich, fatty or supplementing foods. In addition, cigarette smoking, or working in a very dry or dehumidified environment can dry the Lungs, and by extension, the Large Intestine.

Diet

The type of food consumed and the way it is consumed are important factors in the genesis of constipation. The western diet is, for the most part, heavy in protein and fat, and light on dietary fiber. Dietary fiber, from the cell walls of grains, vegetables and fruits is largely composed of cellulose, and is indigestible in humans. Fiber acts as a bulking agent, increasing the volume of a stool, thus triggering the stretch receptors in the intestinal wall. This in turn stimulates intestinal peristalsis and decreases transit time of waste material through the intestines. Insufficient fiber and a high proportion of fat, which slows transit time, contribute significantly to sluggish movement of waste material through the bowel, and thus constipation. This tendency to sluggishness is compounded by the lack of physical activity and hours of sitting, common in today's office environment.

In TCM terms, the typical western diet is heating and overly supplementing. People often overeat as well, leading to food stagnation. An excess of heating and drying foods, such as chilies, coffee and bitter substances, can dry the Intestines and damage yin. Large quantities of diuretic substances, such as coffee and cola drinks, can promote excessive urination and an uneven distribution of fluids, causing dryness in the Intestines.

Yang deficiency usually gives rise to diarrhea, however, in some patients chronic constipation may result. This type of constipation is due to the combined effects of the constricting Cold and lack of yang propulsion through the Intestines. Cold natured or raw foods can introduce Cold and weaken Spleen qi and yang. Some drugs weaken the Spleen and deplete Spleen qi and yang. Prolonged use of purgative laxatives, such as senna or cascara, will eventually weaken yang. Antibiotics and the antiretroviral drugs and protease inhibitors used to treat HIV infection are also Cold in nature and weaken the Spleen. Reduced food intake as a result of strict dieting, or prolonged starvation or digestive insult, seriously damages Spleen yang.

Emotion

The Stomach and Intestines rely on the smooth passage of Liver qi for their orderly function, and to some extent on the unimpeded descent of Lung qi. A combination of stress, which disrupts Liver qi, and inactivity or a sedentary occupation which weakens Lung qi and causes a general sluggishness of qi, can lead to a general derangement of gastrointestinal function and sluggishness of qi movement through the Intestines.

Liver qi stagnation is a frequent cause of internal stagnant Heat, as the pressure buildup of the stagnant qi can easily transform to Heat, especially if the diet is rich in heating foods.

Prolonged Liver qi stagnation can also contribute to the generation of Phlegm which can accumulate in the Intestines and contribute to the constipation. The Phlegm can be generated by Liver qi invading and weakening the Spleen, or by the retarded movement and distribution of fluids, which over time congeal into Phlegm.

Failure of Lung qi to descend properly can also contribute to constipation by not assisting Large Intestine qi descent. This can be seen in the constipation that often accompanies or follows an upper respiratory tract infection and cigarette smoking. The emotions experienced following the death or absence of a parent or loved one, a sudden change from a comfortable routine to an unfamiliar one, can obstruct Lung qi. The Lung system, which incorporates the Large Intestine, is affected and qi begins to knot, causing a tendency to constipation.

Similarly, if Lung qi has been weakened for some reason, such as lack of exercise or postural problems, the feeble Lung qi may not descend, contributing to a failure of Large Intestine qi descent.

Anxiety, embarrassment or denial associated with bowel habits can contribute to constipation. Children unwilling to have a bowel movement at school, for example, may ignore the natural urges to such an extent that the stretch receptors in the bowel wall are reset. As a consequence, the intestines fail to respond to the presence of a stool. The peristaltic response and urge to defecate diminish. This habitual behavior can lead to chronic and difficult-to-rectify constipation.

Phlegm

Phlegm can contribute to constipation because its sticky glutinous nature easily clogs the qi mechanism and disrupts the descent of Stomach and Large Intestine qi. When Phlegm is implicated in constipation, it is frequently associated with Liver qi stagnation, and it is usually the qi stagnation that weakens the Spleen and slows the distribution of fluids, encouraging them to congeal into Phlegm.

Phlegm can also be generated by chronic food stagnation, that is, an ongoing tendency to overeating, in particular overeating rich or otherwise congesting and Phlegm generating foods. It is common for patients with Phlegm type constipation to be overweight. Phlegm type constipation can have a constitutional component and may run in families. When constitutional, the tendency to constipation or sluggish stools will probably be evident from childhood.

Yin, Blood and fluid deficiency

Yin, Blood and fluid deficiency patterns are very common causes of chronic constipation and are due to insufficient lubrication of the bowel by yin fluids, including Blood. Yin and Blood deficiency patterns frequently occur in elderly patients, whose yin is naturally depleted by aging, and in postpartum women. Yin deficiency constipation can also follow a febrile illness, such as the yang ming syndrome above, or Lung Heat, which has consumed and damaged yin fluids in general. Damage to yin fluids can also result from fluid loss or excessive drying following over-enthusiastic treatment for some other disorder. Typical examples include causing excessive sweating for an external pathogenic surface invasion, excess diuresis for edema, or the use of too many or inappropriate bitter parching or warming herbs.

Blood deficiency occurs following hemorrhage, prolonged breast feeding, excessive sweating or if there is insufficient protein in the diet. It frequently complicates Spleen qi deficiency.

Qi and yang deficiency

Qi and yang deficiency types of constipation are due to a lack of qi movement in the Intestines, compounded in the case of yang deficiency by Cold which ‘freezes and constricts’ movement through the Intestines, further slowing the passage of stools. The stools of qi and yang deficiency constipation are usually moist and loosely formed; the main characteristic is the lack of peristalsis or desire to defecate. Qi deficiency, usually of the Lung and Spleen, can be the result of lack of exercise or excessive exercise, overwork, overconsumption of cold, raw or Damp inducing foods, excessive worry or mental activity. Lung qi deficiency may result from a combination of poor posture, shallow breathing, or unexpressed or prolonged grief or sadness. Qi deficiency can also result from consumption of qi following a prolonged illness. Smoking cigarettes may in the short term assist in opening the bowels by dispersing Lung qi and therefore Large Intestine qi, but will eventually weaken Lung qi and introduce Heat that will dry the Lungs and Intestines, contributing to constipation.

The etiology of yang deficiency is similar to qi deficiency, however it is more frequent in older patients whose yang is in natural decline. Spleen yang is weakened by excessive consumption of cold raw foods or cold drugs. It may develop from deterioration of Spleen qi deficiency. Additional factors are prolonged or serious illness, gastro-intestinal surgery or excessive ingestion of very cold substances. Fad dieting and prolonged starvation, seriously damages Spleen yang. Kidney yang declines with age, exposure to cold, multiple pregnancies and chronic illness.

Lack of exercise

Insufficient physical activity can contribute to constipation. People who sit all day tend to have systemically sluggish qi, which impedes movement of qi and thus waste materials through the Intestines. Similarly, lack of exercise weakens the Spleen and Lungs. When the Spleen is weak, the qi mechanism is easily disrupted, Stomach qi fails to descend properly and qi movement through the abdomen slows. Weak Lung qi may fail to assist the normal descent of Large Intestine qi.

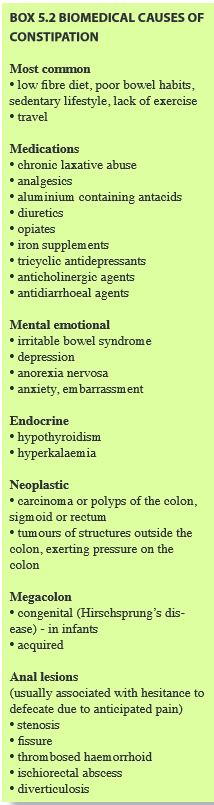

Medications

Certain medications are frequently implicated in constipation. The most notorious are the opiates, including codeine. Some more commonly used substances may also cause constipation, and can be easily overlooked during diagnosis. These include iron supplements, diuretics and antidepressants. See Box 5.2.

DIAGNOSIS

Of the excess patterns, the most frequent cause of constipation in the western world is insufficient dietary fiber, with consequent lack of bulk in the stool. With rich, high density, supplementing foods, like fats and meat, colonic transit time is slowed and food stagnates. As noted previously, this type of diet can lead to accumulation of food, Dampness and Heat, in the Liver, Spleen, Stomach and Intestines. Damp Heat affecting the Liver can also aggravate any tendency to Liver qi stagnation, which in turn can generate more Heat and so on. Herbs and acupuncture can be useful in speeding recovery, but the most important aspect of treatment is to reduce the excess by modifying the diet.

The deficient patterns are characterized by lack of moisture and intestinal lubrication (‘not enough water to float the boat’), or weakened intestinal propulsion.

There are several traps to be avoided in the analysis and treatment of constipation. Firstly, it is important to clearly establish that the patient is truly constipated and without unreal expectation of what regularity implies.

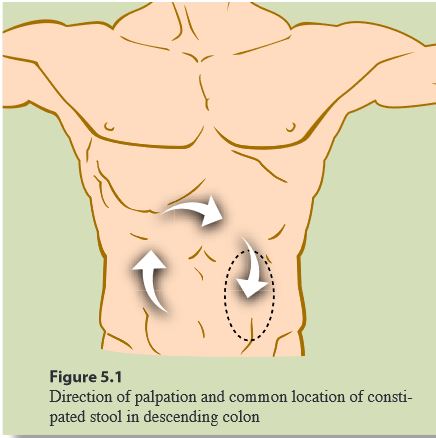

Always palpate the abdomen to see if any masses can be detected. Patients with impacted feces may present with diarrhea (‘spurious’). Abdominal palpation is also useful when a patient presents with a confusing or complicated pattern or mixture of patterns. The abdominal findings can guide the initial treatment priority in such cases. A patient with an abdomen that is tense firm or tight, and that resists the palpating hand, i.e. is worse for pressure, most likely as an excess pattern. This is consistent even in a patient who may otherwise appear deficient or weak. On the other hand, a patient with an abdomen that is flabby or soft, and that likes, or at least does not dislike pressure on the abdomen most likely has a deficient pattern as the main feature, regardless of the robust nature or excess appearance of the patient.

TREATMENT

Acute constipation is easy to treat and will generally resolve satisfactorily within a few days. Chronic constipation is more difficult and often requires prolonged treatment for adequate results. The situation is complicated by the fact that many patients will have been using laxatives, frequently inappropriately. For example, patients with deficiency types of constipation, such as Blood or yin deficiency which need to be nourished and moistened often take bitter cold purgative herbs like senna or cascara, as they are freely available over the counter in pharmacies and drug stores and are recommended for all types of constipation. Prolonged use of these substances weakens the Spleen, Stomach and Intestines and can significantly inhibit the patient’s response to the treatment. Patients taking these laxative substances have to be weaned off them slowly as the appropriate treatment takes effect. In all the chronic types, however, persistence is the key to success, and prolonged treatment will usually be successful. Our aim of treatment should not be to keep treating or medicating patients ad infinitum, but to re-establish normal functioning. In practice, dietary and life changes are usually necessary to maintain long term results, in both the excess and deficiency patterns.

Therefore it is important to educate as well as provide treatment. The two free therapies, diet and exercise, can be introduced and encouraged, and these will, in many cases, be successful alone in alleviating constipation.

Diet

Diet is such an important part of maintaining a healthy bowel habit and preventing constipation that it should be considered the primary treatment for many people. The foods and approaches outlined in Chapter 26 are suitable for the dietary treatment of constipation.

Exercise

Moderate exercise stimulates the Spleen and Stomach, strengthens the Lungs, and improves the functioning of the qi mechanism. This in turn has a stimulating effect on the harvesting of qi from food and the movement of the residue through the Intestines. Regular daily exercise, 30 minutes of sustained walking is often enough, is beneficial for everyone, except those in extreme debility. Exercise is especially beneficial for patients with qi stagnation and Spleen deficiency patterns. In fact, for patients with qi stagnation patterns, often increasing exercise levels alone will encourage regular bowel habits.

CAUTIONS

Recent onset of constipation in middle aged and elderly people may suggest neoplasms of the bowel. Extrinsic malignancy invading or compressing the bowel, lymphoma or carcinoma in the genitourinary system, should be considered.

Depression and purgative abuse are often unrecognized as factors in chronic constipation. Changes in the shape of the stools, or slender or ribbon like stools, may suggest a physical obstruction in the bowel.

Please see William Maclean’s Clinical Handbook of Internal Medicine, Volume 2 for a detailed discussion of herb and formula recommendations. For compliance reasons those sections cannot be presented by Mayway.