A Brief History of Traditional Chinese Herbal Medicine in America

Chinese medicine has a long history here, even before the Chinese ever set foot in America. During America’s colonial period, Chinese tea, and herbs such as rhubarb, cinnamon, cardamon, and camphor crossed the ocean to the new world, just as Appalachian wild ginseng went east. White Americans learned about Traditional Chinese Medicine not only through the herbs they consumed but also through European and American merchants, missionaries, and medical scientists who went to China, studied, and sometimes adopted Chinese therapeutic practices. In fact, by the mid-1700s the Ben Cao Gang Mu, the famous sixteenth century Chinese pharmacopoeia, had already been translated into English. Americans of this era already relied on plant-based medicines, so Chinese herbs weren’t strange at all.

In the 1850s Gold Rush era, Chinese immigrants came to America in significant numbers and of course brought their health practices with them. Every immigrant brought some herbal medicine in their luggage. The herbalists who came, like most other 19th century Chinese immigrants, were almost exclusively Cantonese people (so southern Chinese) from the Pearl River Delta areas. By this time white Americans were accustomed to consulting with nonwhite healers, whether Native American, African, or Chinese. When I think about it, this might have been one of the only interaction points that was more pleasant and less tinged with racism. Many Chinese practitioners became famous and well-respected by whites, and over time, ordinary Americans learned to associate Chinese medicine with magical healing powers.

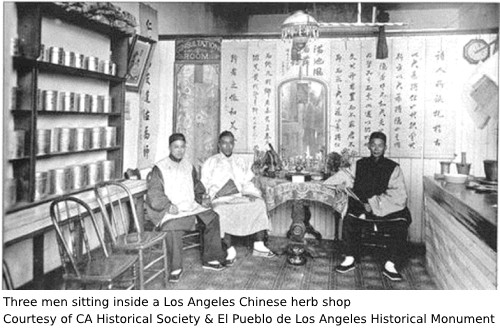

Herbs were imported by Chinese merchants, some of whom were Chinese medicine doctors themselves, and many became very wealthy and leaders in the Chinese community. They also sold herbs to their fellow practitioners across the country. Those herbalists outside of cities primarily served the small Chinese communities that sprang up in mining camps and along the route of the Transcontinental Railroad, treating the Chinese workers and even some whites. You can read more about and sometimes even visit the preserved clinics of famous frontier doctors like Doc Ing Hay of John Day, Oregon and Dr. Yee Fung Cheung, who treated out of his Chew Kee Store of Fiddletown, California. Especially in these far-flung places, herb shops were often the center of Chinese immigrant life—they not only provided medical help, but likely served as the general store, the post office, the bank, and even the place for community worship.

Unfortunately, when the easy gold mining dried up and the Transcontinental Railroad was finished, whites struggled to find work. Generally keeping to themselves, whether by choice or in reaction to prejudicial hostilities, the Chinese became scapegoats when menial labor became the only work available. Chinese had always received less pay for the same work, like toiling in fields or fisheries, and had been willing to do so-called women’s work like cooking and laundry, but now were resented for “taking away jobs from whites”. Racism and resentment became rampant. Chinese communities all over the country were burned down, people were beaten and driven from their homes, and often murdered. Survivors mostly fled to the safety of the larger Chinatowns, like in San Francisco.

This discrimination was so prevalent that in 1882 Congress passed the first in a series of exclusion acts, effectively stopping immigration from China. This is still the only set of laws in U.S. history to target the people of a specific country. These exclusionary laws only allowed for certain types of Chinese to come to America--the wealthy, diplomats, clergymen, students, and a few others. This gave rise to human trafficking, especially of women for prostitution, and caused a subsequent decline in the Chinese population in the U.S. This lasted well into the mid-twentieth century, which profoundly affected the makeup and society of the remaining Chinese population. A consequence was the so-called “bachelor society” that was created as tens of thousands of Chinese men never again saw the families they had left behind in China.

These discriminatory laws also affected and reduced trade, making many herbs so difficult to get that many Chinese herbalists began growing them themselves and searching for equivalent native herbs.

Like most people and small businesses, Chinese herb shops struggled during the Great Depression of the late 1920s. Chinese, along with other Asians, were relegated to the bottom of society and continued to be discriminated against when it came to work of every kind. Fortunately, the clan, mutual-aid and Benevolent Associations in Chinatowns provided enough assistance to protect their residents from starvation, and legal help in applying for government aid. Although Chinatowns generally began to prosper in the late 1930s because of the end of prohibition and a boom in tourism, mid-century wars in Asia further disrupted supply lines, making it difficult to restock herb drawers and shelves.

During WWII and the Cold War, America recruited scientists—including biomedical doctors-- through new immigration policies and educational exchange programs. Refugees from China in the 1940s and American-born Chinese began to pursue careers in licensed medical professions rather than practice traditional Chinese Herbal Medicine. As the American Medical Association (AMA) came into prominence, pushing forward its western science and the regulation of the medical marketplace since the Progressive Era, confidence in alternative therapies was eroded, and many Chinese herb shops shuttered their businesses during this time.

With the lack of immigration and the low number of Chinese women in America (even by the 1940s, they were only about 30% of the Chinese population because the old bachelors had died off and most were American born), Chinese communities in most small towns dwindled and then vanished as their populations died off. Even in Chinatowns with second and third generations of American born Chinese, these children mostly did not continue their family herb businesses. Although the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act had been repealed in 1943, visas for Chinese immigrants were still limited to about 100 per year. It wasn’t until the signing of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, that a fresh wave of Chinese immigrants came to America and revived communities as well as the business of Chinese herbs. Our parents opened their herb shop in 1969 after their own immigration journey. At the time, most of the other herb shops in San Francisco Chinatown were run by very old men. When we were kids, only a few shops had a second generation working in or running them: I remember Superior Trading Company, the Great China Art Company, and Tai Sang Tong, all located on Washington Street. Sadly, today all 3 shops no longer exist, being unable to enlist a third generation to keep the family business going.

In the 1970s, a countercultural backlash to western biomedical hegemony, warming relations between the U.S. and China, and a seminal article by James Reston of the New York Times helped popularize acupuncture among American patient-consumers. The Licensure of Acupuncture in Oregon, Maryland, and Nevada in 1973, and then California in 1976 helped to support the growth of the acupuncture profession, which relied heavily on treatment with herbs. Although a growing number of the acupuncturists were white, many became expertly trained in the use of Chinese herbs. Chinese herbs were imported almost exclusively through Hong Kong until the mid-1990s, and Chinese herb businesses were still predominantly owned and operated by Cantonese.

Another wave of Chinese immigrants in the 1990s, including of TCM doctors from China, heralded a renaissance in the use of traditional Chinese herbal medicine, leading to a wider range of herbs and patent medicines being imported into the U.S. The use of “patent” or proprietary herbal medicines in pill, tablet, and capsule form had grown since the 1980s because of their convenience and as more medicines from China, Japan, and other parts of Asia came into the market. Significantly, in 1994 the United States Food & Drug Administration (FDA) passed the Dietary Supplement Health Education Act (DSHEA) which defined and regulated all dietary supplements, including Chinese herbs.

Interestingly, the now multi-billion-dollar U.S. dietary supplement industry uses about 95% of the Chinese herbs imported into the U.S. Commonly known Chinese herbs such as Astragalus root, Lycium fruit (now popularly known as “Goji Berries”), and Licorice root are marketed as dietary supplements rather than as traditional Chinese herbs. As usage by the public has increased, there have been incidents of adverse events from wrongly prescribed and misidentified Chinese herbs that have led to the FDA restricting or even banning importation and usage of certain herbs. Issues of sustainability (such as endangered species) and safety (such as toxic chemical constituents, heavy metals, and pesticides) have also developed that pose challenges to the industry.

Today in America, traditional Chinese herbal medicine is widely accepted as complementary to western allopathic medicine, with over 30,000 licensed acupuncturists in practice across the country. Thousands of peer-reviewed research articles from around the world attest to the value of TCHM in treating disease and benefiting human health. In 2015, millions of Chinese around the world watched with pride as Chinese researcher Dr. Tu Youyou received the Nobel Prize for her research of a Chinese herb in treating malaria.

Through it all, Chinese herb shops have weathered the ups and downs of history and have persevered. A younger generation, mostly made up of recent immigrants, have taken up the mantle in Chinatowns and in smaller Chinese enclaves to provide familiar remedies to an aging community. Although the use of Chinese herbs has declined among younger, American-born and immigrant Chinese, Chinese herb shops still exist across the US, and herbs and herbal products can be found in Asian grocery stores and western natural health retailers. Chinese herbs can now also be easily purchased online, treating health in even far-flung, remote places where maybe a Chinese mining camp once thrived. As the popularity and accessibility of traditional Chinese herbal medicine in America continues to evolve, it is heartening to see how this ancient medicine, once used solely by an outcast, disenfranchised people, has come to finally be embraced by its adopted land.

Yvonne Lau has been the President of Mayway Herbs since 1997 but has worked in the family Chinese herb business since childhood. She first visited China in 1982, and still travels there annually for business and pleasure. She has had the good fortune and honor to work with many people both in China and the US who are passionate about Chinese Medicine and about herb quality.

Yvonne Lau has been the President of Mayway Herbs since 1997 but has worked in the family Chinese herb business since childhood. She first visited China in 1982, and still travels there annually for business and pleasure. She has had the good fortune and honor to work with many people both in China and the US who are passionate about Chinese Medicine and about herb quality.

Yvonne has also been active as the Vice President of the Chinese Herb Trade Association of America since 1998, a trade group founded in 1984 representing over 300 Chinese herb importers, distributors, and retailers primarily in California. She chairs the Regulatory Compliance Committee for the Association, and in this role has lectured about Good Manufacturing Practices and best business practices, as well as organized and moderated meetings between regulatory agencies and the Association.

Sources

- Shelton, T.V. (2019). Herbs and Roots: A History of Chinese Doctors in the American Medical Marketplace. Yale University Press.

- Tchen, J.K.W. (1984). Genthe’s Photographs of San Francisco’s Old Chinatown. Dover Publications, Inc.

- Lee. A.W. (2001). Picturing Chinatown: Art and Orientalism in San Francisco. University of California Press.

- “The Exclusion of Chinese Women, 1870-1943, Chan, S.C. https://www.lcsc.org/cms/lib/MN01001004/Centricity/Domain/81/TAH%202.pdf

- “History of Chinese Americans.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation (30 July 2022), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Chinese_Americans

- “History of Chinese Americans in San Francisco.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation (14 August 2022), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Chinese_Americans_in_San_Francisco

- “Chinatown, San Francisco.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation (13 August 2022), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinatown,_San_Francisco

- “1906 Earthquake.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation (22 August 2022), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1906_San_Francisco_earthquake

- “List of streets and alleys in Chinatown, San Francisco.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation (11 April 2022), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_streets_and_alleys_in_Chinatown,_San_Francisco

- “Chew Kee Store Museum (no. 107 Point of Historic Interest).” Sierra Nevada Geotourism. https://sierranevadageotourism.org/entries/chew-kee-store-museum-no-107-point-of-historic-interest/241a59d7-73b3-4acc-8483-289344851ca2

- “Ing Hay (“Doc Hay”) (1862-1952).” Varon, J., Oregon Encyclopedia. https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/ing_doc_hay_1862_1952_/#.YwlvoHbML50

- “Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation (17 August 2022), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_Consolidated_Benevolent_Association

- “Miriam Lee” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation (9 June 2022), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miriam_Lee